| COUNSELOR'S CORNER |

|

Tuesday, April 26 2016

Through a Glass, Darkly

Ministry to the mentally ill.

Amy Simpson

When I was 15 years old, my mother picked me up at school to take me to a dental appointment. In the car, I could tell immediately that she wasn't functioning normally—she was headed for another "episode." She drove nervously, struggling to recognize her surroundings. She was silent except when I forced conversation, and when she did speak, her speech was slow and seemed to require deliberation.

It was as if half of her had already shrunk into some unknown place, and the other half was not sure whether to follow or to maintain her grip on the reality of her daughter and a trip to the dentist.

I asked Mom if she had taken her medication that day. Her answer was not straightforward, but it was clear that she was not fully medicated and stable. So with one part of my brain, I prayed for a safe trip to the dentist. With another part, I employed a technique used by many people who feel powerless in the face of an unnamed enemy: I acted as if nothing was wrong.

At the dentist's office, when my name was called, I left my mother in the waiting room and went back for my appointment. After half an hour or so with the dentist, I returned to my mom, who didn't look at me.

"Mom, it's time to go," I said. "I'm finished." I received no response of any kind. Suddenly I realized my instincts had been right: something indeed was wrong with Mom … again. And it was up to me to help her.

I touched her arm and gently tried to shake her back to awareness, with no results. She was rigidly catatonic, immovable, staring into space and clutching her purse in her lap with clenched hands—in a waiting room full of strangers.

After a couple of quiet attempts to rouse her, I began to attract attention. People stared at me as I tried to get her to respond. When she wouldn't move, I realized I needed to call my dad at work for help.

As everyone in the room continued to stare, I walked to the reception desk and asked the woman behind the counter—who was also staring—if I could use the phone.

"No, there's a pay phone around the corner," she said. When I explained that I needed to call my dad for help, I didn't have change for the phone, and it would be a local call, she still refused. So I went back to my mom and wrestled with her rigid arms, pulling them aside enough to get into her purse to find a quarter for the phone. I went back to the receptionist to ask if she could keep an eye on my mom while I went to use the pay phone. She shrunk back in horror: "Is she dangerous?"

After assuring the receptionist that my motionless mother was not about to attack her, I called my dad and then returned to sit next to my mom till he got there. The receptionist and the people in the waiting room took turns staring at my mom, glancing at me, and studying the floor. No one asked if I needed help.

In the years since, that incident has become for me a symbol. The way people in that waiting room responded to my family's public crisis is the way I've seen people—including those in the church—respond to serious mental illness. They didn't know what to do for my mom or anyone associated with her. So they did nothing.

Though I didn't know it at the time, my mother has schizophrenia. As often happens with schizophrenics, she had not been faithfully taking her anti-psychotic drugs and had lost touch with reality. Dad and I took her to the hospital for another of her psychiatric stays and restabilization on medication.

Amy is a senior editor of Leadership Journal and editor of GiftedforLeadership.com.

Wednesday, March 23 2016

I have been doing a lot of thinking about session length lately. Over the past several years I have followed the trend of decreasing my session length to 45 minutes. I remember when sessions were standardized at 50 minutes when I started practicing 36 years ago. The idea was to see people for 50 minutes then have a 10 minute break between sessions, which worked pretty well for most people. Intakes were a little difficult to fit in that time for most people and often needed a longer time period. The biggest challenge was couples. Trying to fit a session with a couple into 50 minutes was always difficult and fitting them into 45 minutes, which is now the standard time that third party reimbursers ususally pay for, is even harder.

So with that in mind I thought I would adjust session length to 75 minutes to 90 minutes. Seventy-five minutes seems to work much better with most of the people I would with including couples and individuals and we don't seem rushed. Then I have 15 minutes between sessions if needed. People seem to treat time differently. Previously most of my clients came for weekly sessions but now they tend to come biweekly or longer, which actually works better for most people and especially couples giving them time to work on issues between sessions.

From a financial perspective it is more economical for clients to come less frequently and be seen longer at each session since I charge the same for 75 minute to 90 minute sessions as I used to charge for 45 minute sessions. I suppose I could charge more but I would rather take my time with each couple or individual and pass the cost savings on to them. For them it is like they get two sessions for the price of one each time and I get the luxury of a longer amount of their time when I have them, which is especially helpful since it is often difficult for clients and espeically couples to find time to be a couple let alone come for counseling.

I have also noticed the relaxed pace helps both me and my clients relax as well. I am not as sensitive to watching the time and being careful not to cross into the next session. This makes sessions seem rushed and often results in items getting moved to the next session, which due to client's time constraints may not occur with the frequence it once did.

This process may not work for all counselors but I find it effective for me and the folks I work with.

Tuesday, June 09 2015

This ad will not display on your printed page.

Christianity Today, June, 2015

Understanding the Transgender Phenomenon

The leading Christian scholar on gender dysphoria defines the terms—and gives the church a way forward.

Mark Yarhouse / posted June 8, 2015

Image: Tom Maday

I still recall one of my first meetings with Sara. Sara is a Christian who was born male and named Sawyer by her parents. As an adult, Sawyer transitioned to female.

Sara would say transitioning—adopting a cross-gender identity—took 25 years. It began with facing the conflict she experienced between her biology and anatomy as male, and her inward experience as female. While still Sawyer, she would grow her hair out, wear light makeup, and dress in feminine attire from time to time. She also met with what seemed like countless mental-health professionals as well as several pastors. For Sawyer, now Sara, transitioning eventually meant using hormones and undergoing sex reassignment surgery.

Sara would say she knew at a young age—around 5—that she was really a girl. Her parents didn’t know what to do. They hoped their son was just different from most other boys. Then they hoped it was a phase Sawyer would get through. Later, two pastors told them that their son’s gender identity conflicts were a sign of willful disobedience. They tried to discipline their son, to no avail.

Sara opened our first meeting by saying, “I may have sinned in the decisions I made; I’m not sure I did the right thing. At the time, I felt excruciating distress. I thought I would take my life. What would you have me do?” The exchange was disarming.

I have worked with people like Sara for more than 16 years. Although most of my published research and clinical practice is in the area of sexual identity, I regularly receive referrals to meet with people who experience conflicts like Sara’s. The research institute I direct, housed at Regent University in Virginia, published the first study of its kind on transgender Christians a few years ago. My experiences counseling children, adolescents, and adults have all compelled me to further study gender dysphoria.

From this research and counseling background, I hope to offer the Christian community a distinctly Christian response to gender dysphoria.

Defining the Terms

First, let’s define our terms. “Gender identity” is simply how people experience themselves as male or female, including how masculine or feminine they feel. “Gender dysphoria” refers to deep and abiding discomfort over the incongruence between one’s biological sex and one’s psychological and emotional experience of gender. Sara would say she lived much of her life as a woman trapped inside a man’s body. When a person reports gender identity concerns that cause significant distress, he or she may meet criteria for a gender dysphoria diagnosis.

The previous version of the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual included the diagnosis “gender identity disorder.” It highlighted cross-gender identity as the point of concern. The newest version refers instead to “gender dysphoria,” moving the discussion away from identity and toward the experience of distress. A lack of congruence between one’s biological sex and gender identity exists on a continuum, so when diagnosing gender dysphoria, mental-health professionals look at the amount of distress as well as the amount of impairment at work or in social settings.

It is hard to know exactly how many people experience gender dysphoria. Most of the research has been on “transsexuality.” The term refers to a person like Sara who wishes to or has identified with the opposite sex, often through hormonal treatment or surgery. The American Psychiatric Association estimates the number of transsexual adults as low as 0.005 to 0.014 percent of men and 0.002 to 0.003 percent of women. But these are likely underestimates, as they are based on the number of people who visit specialty clinics.

The highest prevalence estimates come from more recent surveys that include “transgender” as an option. “Transgender” is an umbrella term for the many ways people experience a mismatch between their gender identity and their biological sex. So not everyone who is transgender experiences significant gender dysphoria. Some people say their gender resides along a continuum in between male and female or is fluid. They do not tend to report as much distress. Prevalence here has ranged from 1 in 215 to 1 in 300.

This means that transgender people are much more common than those formally diagnosed with gender dysphoria, but not nearly as common as those who identity as gay or lesbian, which is 2 to 4 percent of the US population.

While on the topic of homosexuality, let me clarify that gender dysphoria and transgender issues are not about having sex or attraction to the same sex; they are about an experiential mismatch between one’s psychology and one’s biology. People often confuse the two, likely due to transgender being a part of the larger lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discussion.

Psychologists and researchers don’t know what causes gender dysphoria. The most popular theory among those who publish on this topic is the brain-sex theory. It proposes that the brain maps toward male or female, which in nearly all cases corresponds with various biological indicators of sex: chromosomes, gonads, and sex hormones. In rare instances, the normal sex differentiation that occurs in utero occurs in one direction (differentiating toward male, for example), while the brain maps in the other direction (toward female). Several gaps remain in the research behind this theory, but it nonetheless compels many professionals.

Recently a mother came to me, worried about her 7-year-old son. “What can we do?” she asked. “Just last week a woman at the park said something. I couldn’t believe she had the nerve. I’m afraid the kids at school might do worse.”

The mother noted that her son’s voice inflection seemed more like a girl’s and that he pretended he had long hair. Over the past weekend, he had grabbed a towel and put it around his waist and said, “Look, Mom, I’m wearing a dress just like you!”

Gender dysphoria and transgender issues are not about having sex or attraction to the same sex; they are about an experiential mismatch between one’s psychology and one’s biology.

Whether and how to intervene when a child is acting in ways typical of the opposite sex is a controversial topic, to say the least. It’s important to remember that in about three of four of these cases, the gender identity conflict resolves on its own, lessening or ceasing entirely. However, about three-fourths of children who experience a lessening or resolution go on as adults to identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual—a fact that psychologists don’t fully understand at this time.

What happens to children when their gender identity conflict continues into adulthood? Psychiatrist Richard Carroll proposes that they face four outcomes: (1) live in accordance with one’s biological sex and gender role; (2) engage in cross-gender behavior intermittently; (3) adopt a cross-gender role through sex reassignment surgery; or (4) unresolved (the clinician has lost contact with the person and doesn’t know what happened).

Sara pursued the third outcome. Bert pursued the second. He’s a biological male who for years has engaged in cross-gender behavior from time to time to “manage” his gender dysphoria. He wears feminine undergarments that no one apart from his wife knows about. He has grown his hair out and may wear light makeup, and this has been enough to manage his dysphoria.

Crystal pursued the first option. She has experienced gender dysphoria since childhood. It has ebbed and flowed throughout her life, but she’s able to cope with it. She presents as a woman and has been married to a man for 12 years. He is aware of her dysphoria.

Few studies have shown that therapy successfully helps an adult with gender dysphoria resolve with their biological sex. This may be one reason professionals generally support some cross-gender identification in therapy.

As someone with gender dysphoria considers different ways to cope, what might the Christian community distinctly offer them?

Three Lenses

To answer this question, let me first describe three cultural lenses through which people tend to “see” gender dysphoria.

Lens #1: Integrity. The integrity lens views sex and gender and, therefore, gender identity in terms of what theologian Robert Gagnon refers to as “the sacred integrity of maleness or femaleness stamped on one’s body.” Cross-gender identification is a concern because it threatens to dishonor the creational order of male and female. Specific biblical passages, such as Deuteronomy 22:5 or 23:1, bolster this view. Even if we concede that some of the Old Testament prohibitions were related to avoiding pagan practices, nonetheless, from beginning to end, Scripture reflects the importance of male-female complementarity set forth in creation (Gen. 2:21–24).

The theological foundation of the integrity lens raises the same kind of concerns about cross-gender identification as it raises about homosexuality. Same-sex sexual behavior is sin in part because it doesn’t “merge or join two persons into an integrated sexual whole,” writes Gagnon. “Essential maleness” and “essential femaleness” are not brought together as intended from creation. When extended to transsexuality and cross-gender identification, the theological concerns rest in what Gagnon calls the “denial of the integrity of one’s own sex and an overt attempt at marring the sacred image of maleness or femaleness formed by God.”

The integrity lens most clearly reflects the biblical witness about sex and gender. While it may be challenging to identify a “line” in thought, behavior, and manner that reflects cross-gender identification, people who see through the integrity lens are concerned that cross-gender identification moves against the integrity of one’s biological sex—an essential aspect of personhood.

It should be noted that some Christians do not put gender dysphoria in the same category as homosexuality. They may have reservations about more invasive procedures; however, they do put gender dysphoria or trying to manage dysphoria in the same class of behaviors that Scripture deems immoral.

Lens #2: Disability. This lens views gender dysphoria as a result of living in a fallen world, but not a direct result of moral choice. Whether we accept brain-sex theory or another account of the origins of the phenomenon, if the various aspects of sex and gender are not aligning, then it’s one more human experience that is “not the way it’s supposed to be,” to borrow a phrase from theologian Cornelius Plantinga Jr.

When we care for someone suffering from depression or anxiety, we do not discuss their emotional state as a moral choice. Rather, the person simply contends with a condition that comes in light of the Fall. The person may have choices to make in response to the condition, and those choices have moral and ethical dimensions. But the person is not culpable for having the condition as such. Here, the parallel to people with gender dysphoria should be clear.

Those who use this lens seek to learn as much as they can from two key sources: special revelation (scriptural teachings on sex and gender) and general revelation (research on causes, prevention, and intervention, as well the lives of persons navigating gender dysphoria). This lens leads to the question: How should we respond to a condition with reference to the goodness of Creation, the reality of the Fall, and the hope of restoration?

Those drawn to the disability lens may value the sacredness of male and female differences; this is implied in calling gender dysphoria a disability. But the disability lens also makes room for supportive care and interventions that allow for cross-gender identification in a way the integrity lens does not.

Lens #3: Diversity. This lens sees the reality of transgender persons as something to be celebrated, honored, or revered. Our society is rapidly moving in this direction. Those drawn to this lens cite historical examples in which departures from a clear male-or-female presentation have been held in high esteem, such as the Fa’afafine of Samoan Polynesian culture.

Whereas the biological distinction between male and female is considered unchangeable, some wish to recast sex as just as socially constructed as gender. To evangelicals, those who want to deconstruct sex and gender norms represent a much more radical alternative to either the integrity or disability lens.

To be sure, not everyone drawn to the diversity lens wants to deconstruct sex and gender. What is perhaps most compelling about this lens is that it answers questions about identity—“Who am I?”—and community—“Of which community am I a part?” It answers the desire for persons with gender dysphoria to be accepted and to find purpose in their lives.

A Distinctly Christian Resource

I believe there are strengths in all three lenses. Because I am a psychologist who makes diagnoses and provides treatment to people experiencing gender dysphoria, I see value in a disability lens that sees gender dysphoria as a reflection of a fallen world in which the condition itself is not a moral choice. This helps me see the person facing gender identity confusion with empathy and compassion. I try to help the person manage his or her gender dysphoria.

When I consider how best to counsel my clients to manage their gender dysphoria, I add the caveat: in the least invasive way possible.

Even as Christians affirm the disability lens, we should also let the integrity lens inform our pastoral care. That lens represents a genuine concern for the integrity of sex and gender, and the ways in which maleness and femaleness help us understand the nature of the church and even the gospel.

Yet we should reject the teaching that gender identity conflicts are the result of willful disobedience or sinful choice. The church can be sensitive as questions arise about how best to manage gender dysphoria in light of the integrity lens. And we can recognize that we live in a specific cultural context, and that many gender roles vary from culture to culture. When I consider how best to counsel my clients to manage their gender dysphoria, however, I add the caveat: in the least invasive way possible.

Christians can also acknowledge how the diversity lens affirms the person by providing an identity not addressed by the other two lenses. The diversity lens emphasizes the importance of belonging. We must remember that the transgender and broader LGBT community are attractive because they answer the bedrock question, “Where do I belong?” Most churches want to be a community where people suffering from any “dysphoria” will feel they belong, for the church is, after all, a community of broken people saved by grace.

A few years ago, my research team at the Institute for the Study of Sexual Identity conducted the first study of its kind on transgender Christians. We collected information on 32 biological males who to varying degrees had transitioned to or presented as women. We asked many questions about issues they faced in their home, workplace, and church, such as, “What kind of support would you have liked from the church?” One person answered, “Someone to cry with me rather than just denounce me. Hey, it is scary to see God not rescue someone from cancer or schizophrenia or [gender dysphoria]...but learn to allow your compassion to overcome your fear and repulsion.”

When it comes to support, many evangelical communities may be tempted to respond to transgender persons by shouting “Integrity!” The integrity lens is important, but simply urging persons with gender dysphoria to act in accordance with their biological sex and ignore their extreme discomfort won’t constitute pastoral care or a meaningful cultural witness.

The disability lens may lead us to shout, “Compassion!” and the diversity lens may lead us to shout “Celebrate!” But both of these lenses suggest that the creational goodness of maleness and femaleness can be discarded—or that no meaning is to be found in the marks of our suffering.

Most centrally, the Christian community is a witness to the message of redemption. We are witnesses to redemption through Jesus’ presence in our lives. Redemption is not found by measuring how well a person’s gender identity aligns with their biological sex, but by drawing them to the person and work of Jesus Christ, and to the power of the Holy Spirit to transform us into his image.

Let’s say Sara walks into your church. She looks like a man dressed as a woman. One question she will be asking is, “Am I welcome here?”

As Christians speak to this redemption, we will be tempted to join in the culture wars about sex and gender that fall closely on the heels of the wars about sexual behavior and marriage. But in most cases, the church is called to rise above those wars and present a witness to redemption.

Let’s say Sara walks into your church. She looks like a man dressed as a woman. One question she will be asking is, “Am I welcome here?” In the spirit of a redemptive witness, I hope to communicate to her through my actions: “Yes, you are in the right place. We want you here.”

If I am drawn to a conversation or relationship with her, I hope to approach her not as a project, but as a person seeking real and sustained relationship, which is characterized by empathy as well as encouragement to walk faithfully with Christ. But I should not try to “fix” her, because unless I’m her professional therapist, I’m not privy to the best way to resolve her gender dysphoria. Rather, Christians are to foster the kinds of relationships that will help us know and love and obey Jesus better than we did yesterday. That is redemption.

If Sara shares her name with me, as a clinician and Christian, I use it. I do not use this moment to shout “Integrity!” by using her male name or pronoun, which clearly goes against that person’s wishes. It is an act of respect, even if we disagree, to let the person determine what they want to be called. If we can’t grant them that, it’s going to be next to impossible to establish any sort of relationship with them.

The exception is that, as a counselor, I defer to a parent’s preference for their teenager’s name and gender pronoun. Even here I talk with the parent about the benefits and drawbacks of what they want and what their teenager wants if the goal is to establish a sustained, meaningful relationship with their child.

Also, we can avoid gossip about Sara and her family. Gossip fuels the shame that drives people away from the church; gossip prevents whole families from receiving support.

Chapters in Redemption

In some church structures, the person’s spiritual life is under the care of those tasked with leading a local congregation. In this case, we have to trust church leadership to do the hard work of shepherding everyone who accepts Christ as Lord and Savior. We trust, too, that God is working in the lives of our leaders to guide them in wisdom and discernment. We trust that meaningful conversations are taking place, and we can add our prayers for any follower of Christ.

In other church settings, it might be us as laypeople who are called into a redemptive relationship with the transgender person. After all, Christians are to facilitate communities in which we are all challenged to grow as disciples of Christ. We can be sensitive, though, not to treat as synonymous management of gender dysphoria and faithfulness. Some may live a gender identity that reflects their biological sex, depending on their discomfort. Others may benefit from space to find ways to identify with aspects of the opposite sex, as a way to manage extreme discomfort. And of course, no matter the level of discomfort someone with gender dysphoria experiences (or the degree to which someone identifies with the opposite sex), the church will always encourage a personal relationship with Christ and faithfulness to grow in Christlikeness.

Certainly we can extend to a transgender person the grace and mercy we so readily count on in our own lives. We can remind ourselves that the book of redemption in a person's life has many chapters. You may be witness to an early chapter of this person's life or a later chapter. But Christians believe that God holds that person and each and every chapter in his hands, until that person arrives at their true end—when gender and soul are made well in the presence of God.

Mark Yarhouse is the Rosemarie S. Hughes Endowed Chair and professor of psychology at Regent University, where he directs the Institute for the Study of Sexual Identity. His most recent book is Understanding Gender Dysphoria: Navigating Transgender Issues in a Changing Culture (IVP Academic).

Tuesday, September 23 2014

This ad will not display on your printed page.

1 in 4 Pastors Have Struggled with Mental Illness, Finds LifeWay and Focus on the Family

Family ministry has LifeWay Research examine how well (or not well) churches address mental health.

Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra

[ posted 9/22/2014 ]

[Updated with Ed Stetzer quotes]

Your pastor is just as likely to experience mental illness as any other American, according to a LifeWay Research survey commissioned by Focus on the Family.

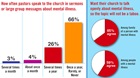

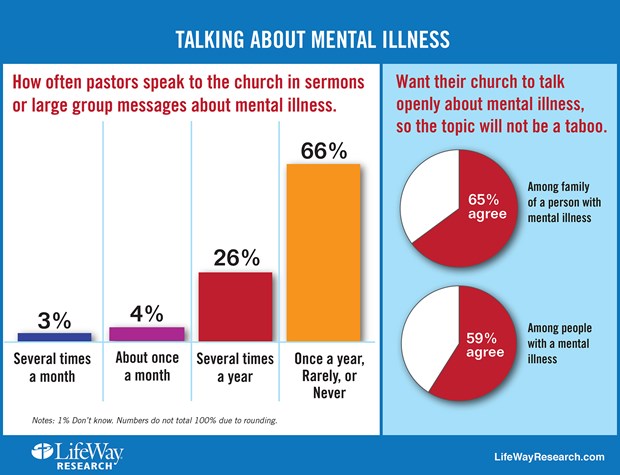

Nearly 1 in 4 pastors (23 percent) acknowledge they have “personally struggled with mental illness,” and 12 percent of those pastors said the illness had been diagnosed, according to the poll (infographics below). One in four U.S. adults experience mental illness in a given year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Recent deaths by suicide of high-profile pastors’ children, including Rick Warren’s son Matthew and Joel Hunter's son Isaac, have prompted increased attention to mental illness from pastors’ pulpits and pens. Warren launched “The Gathering on Mental Health and the Church” this past spring. High-profile pastors, including NewSpring Church pastor Perry Noble, have publicly documented their struggles with mental illness.

“Here’s what we know from observation: If you reveal your struggle with mental illness as a pastor, it’s going to limit your opportunities,” Ed Stetzer, executive director of LifeWay Research, told CT. “What happens is pastors who are struggling with mental illness tend not to say it until they are already successful. So Perry Noble, running a church of 30,000 plus, just last year says ‘I have severe depression.’”

“We have to break the stigma that causes people to say that people with mental illness are just of no value,” he added. “These high-profile suicides made it okay to talk about, but I think Christians have been slower than the population at large to recognize what mental illness is, let alone what they should do."

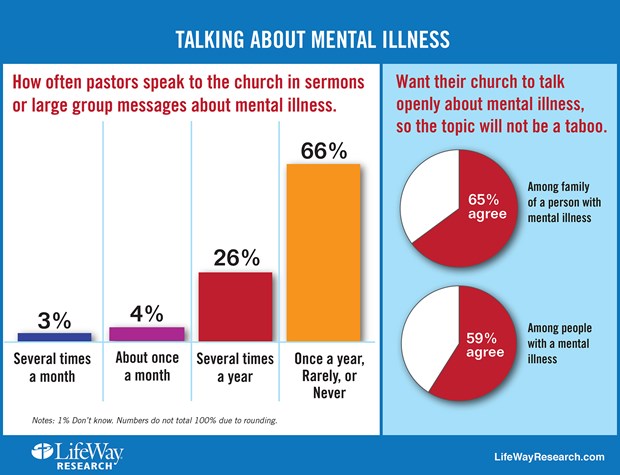

The majority of pastors (66 percent) still rarely or never talk about mental illness in sermons or before large groups, the survey found. About one-fourth of pastors bring up mental illness several times a year, and 7 percent say they tackle it once a month or more.

Image: LifeWay Research Image: LifeWay Research

Struggling laypeople wish their churches dealt with the issue more; 59 percent of respondents with a mental illness want their church to talk more openly about it, as do 65 percent of their family members.

“Our research found people who suffer from mental illness often turn to pastors for help,” Stetzer noted in a news release. “But pastors need more guidance and preparation for dealing with mental health crises. They often don’t have a plan to help individuals or families affected by mental illness, and miss opportunities to be the church.”

Other “key disconnects” uncovered by the study:

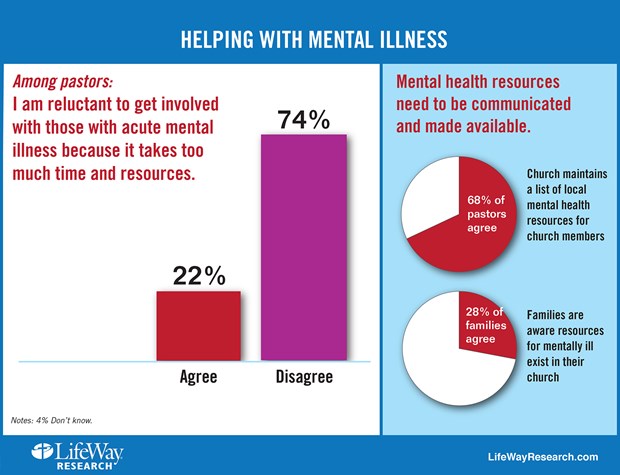

- Two-thirds of pastors (68 percent) say their church maintains a list of local mental health resources for church members. But few families (28 percent) are aware those resources exist.

- Only a quarter of churches (27 percent) have a plan to assist families affected by mental illness, according to pastors. And only 21 percent of family members are aware of a plan in their church.

- Few churches (14 percent) have a counselor skilled in mental illness on staff, or train leaders how to recognize mental illness (13 percent), according to pastors.

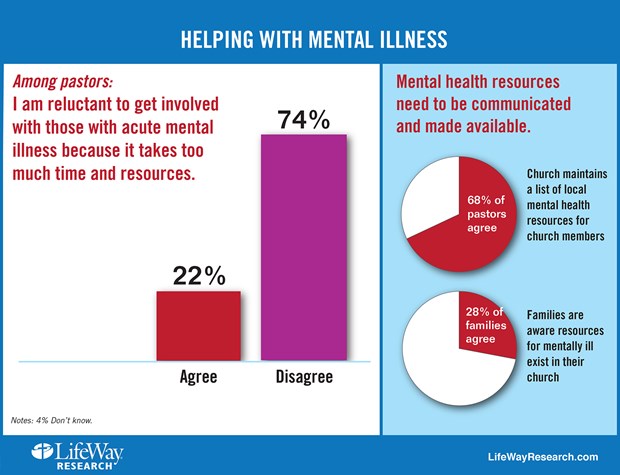

The disconnect isn’t because of a lack of compassion. Most pastors (74 percent) say they aren’t reluctant to get involved with those with acute mental illnesses, and nearly 60 percent have provided counseling to people who were later diagnosed.

Image: LifeWay Research Image: LifeWay Research

Instead, pastors can feel overwhelmed at times with how to properly respond to the mental health needs of members of their congregation; 22 percent said they were reluctant to do more because it took “too much time.”

“Pastors are trained for spiritual struggle. They’re not trained for mental illness,” Stetzer told CT. “And so, what they will often do is pass someone off. I don’t think what that 20 percent says is ‘Forget you,’ but ‘I can’t handle this.’”

The silence at church can lead to a reluctance to share, Atlanta-based psychiatrist Michael Lyles told LifeWay. “The vast majority of [my evangelical Christian patients] have not told anybody in their church what they were going through, including their pastors, including small group leaders, everybody,” he said in the release.

In fact, 10 percent of the 200 respondents with mental illness said they have switched churches after a church’s poor response to them, and another 13 percent stopped going altogether or couldn’t find a church.

But more than half of regular churchgoers with mental illness said they stayed where they were, and half also said that their church has been supportive. One way churches can be supportive, Stetzer suggested to CT, is regular meetings between pastoral staff and the person suffering from mental illness, even as the individual continues to receive consistent medical treatment.

“The Bible is filled with people who struggled with suicide, or were majorly depressed or bi-polar,” said Focus on the Family pyschologist Jared Pingleton in the LifeWay release. “David was totally bi-polar. Elijah probably was as well. They are not remembered for those things. They are remembered for their faith.”

Researchers focused on three groups:

They surveyed 1,000 senior Protestant pastors about how their churches approaches mental illness. Researchers then surveyed 355 Protestant Americans diagnosed with an acute mental illness—either moderate or severe depression, bipolar, or schizophrenia. Among them were 200 church-goers.

A third survey polled 207 Protestant family members of people with acute mental illness.

Researchers also conducted in-depth interview with 15 experts on spirituality and mental illness.

LifeWay's full release is copied below.

CT frequently addresses mental health, including how pastors can guard against mental illness, the spiritual side of mental illness, how Facebook can affect your mental health, and how nothing, not even suicide, can separate people from the love of God. CT also covered Saddleback Church senior pastor Rick Warren’s mental health ministry launch after his son Matthew took his own life in 2013.

-----

Mental Illness Remains Taboo Topic for Many Pastors

By Bob Smietana

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – One in four Americans suffers from some kind of mental illness in any given year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Many look to their church for spiritual guidance in times of distress.But they're unlikely to find much help on Sunday mornings.

Most Protestant senior pastors (66 percent) seldom speak to their congregation about mental illness.

That includes almost half (49 percent) who rarely (39 percent) or never (10 percent), speak about mental illness. About 1in 6 pastors (16 percent) speak about mental illness once a year. And about quarter of pastors (22 percent) are reluctant to help those who suffer from acute mental illness because it takes too much time.

Those are among the findings of a recent study of faith and mental illness by Nashville-based LifeWay Research. The study, co-sponsored by Focus on the Family, was designed to help churches better assist those affected by mental illness.

Researchers looked at three groups for the study.

They surveyed 1,000 senior Protestant pastors about how their churches approaches mental illness. Researchers then surveyed 355 Protestant Americans diagnosed with an acute mental illness—either moderate or severe depression, bipolar, or schizophrenia. Among them were 200 church-goers.

A third survey polled 207 Protestant family members of people with acute mental illness.

Researchers also conducted in-depth interview with 15 experts on spirituality and mental illness.

The study found pastors and churches want to help those who experience mental illness. But those good intentions don’t always lead to action.

"Our research found people who suffer from mental illness often turn to pastors for help," said Ed Stetzer, executive director of LifeWay Research.

"But pastors need more guidance and preparation for dealing with mental health crises. They often don’t have a plan to help individuals or families affected by mental illness, and miss opportunities to be the church."

A summary of findings includes a number of what researchers call ‘key disconnects’ including:

Only a quarter of churches (27 percent) have a plan to assist families affected by mental illness according to pastors.And only 21 percent of family members are aware of a plan in their church. Few churches (14 percent) have a counselor skilled in mental illness on staff, or train leaders how to recognize mental illness (13 percent) according to pastors. Two-thirds of pastors (68 percent) say their church maintains a list of local mental health resources for church members. But few families (28 percent) are aware those resources exist. Family members (65 percent) and those with mental illness (59 percent) want their church to talk openly about mental illness, so the topic will not be a taboo. But 66 percent of pastors speak to their church once a year or less on the subject.

That silence can leave people feeling ashamed about mental illness, said Jared Pingleton, director of counseling services at Focus on the Family. Those with mental illness can feel left out, as if the church doesn’t care. Or worse, they can feel mental illness is a sign of spiritual failure.

"We can talk about diabetes and Aunt Mable’s lumbago in church—those are seen as medical conditions,” he said. “But mental illness--that’s somehow seen as a lack of faith."

Most pastors say they know people who have been diagnosed with mental illness. Nearly 6 in 10 (59 percent) have counseled people who were later diagnosed.

And pastors themselves aren’t immune from mental illness. About a quarter of pastors (23 percent), say they’ve experienced some kind of mental illness, while 12 percent say they received a diagnosis for a mental health condition.

But those pastors are often reluctant to share their struggles, said Chuck Hannaford, a clinical psychologist and president of HeartLife Professional Soul-Care in Germantown, Tennessee. He was one of the experts interviewed for the project.

Hannaford counsels pastors in his practice and said many – if they have a mental illness like depression or anxiety—won’t share that information with the congregation.

He doesn't think pastors should share all the details of their diagnosis. But they could acknowledge they struggle with mental illness.

"You know it’s a shame that we can’t be more open about it,” he told researchers. “But what I’m talking about is just an openness from the pulpit that people struggle with these issues and it’s not an easy answer."

Those with mental illness can also be hesitant to share their diagnosis at church. Michael Lyles, an Atlanta-based psychiatrist, says more than half his patients come from an evangelical Christian background.

"The vast majority of them have not told anybody in their church what they were going through, including their pastors, including small group leaders, everybody," Lyle said.

Stetzer said what appears to be missing in most church responses is "an open forum for discussion and intervention that could help remove the stigma associated with mental illness."

"Churches talk openly about cancer, diabetes, heart attacks and other health conditions – they should do the same for mental illness, in order to reduce the sense of stigma," Stetzer said.

Researchers asked those with mental illness about their experience in church.

A few – (10 percent)—say they’ve changed churches because of how a particular church responded to their mental illness. Another 13 percent ether stopped attending church (8 percent) or could not find a church (5 percent). More than a third, 37 percent, answered, “don’t know,” when asked how their church’s reaction to their illness affected them. Among regular churchgoers with mental illness, about half (52 percent) say they have stayed at the same church. Fifteen percent changed churches, while 8 percent stopped going to church, and 26 percent said, “Don’t know.” Over half, 53 percent, say their church has been supportive. About thirteen percent say their church was not supportive. A third (33 percent) answered, “don’t know” when asked if their church was supportive.

LifeWay Research also asked open-ended questions about how mental illness has affected people’s faith. Those without support from the church said they struggled.

“My faith has gone to pot and I have so little trust in others,” one respondent told researchers.

“I have no help from anyone,” said another respondent.

But others found support when they told their church about their mental illness.

“Several people at my church (including my pastor) have confided that they too suffer from mental illness,” said one respondent. “Reminding me that God will get me through and to take my meds,” said another.

Mental illness, like other chronic conditions, can feel overwhelming at times, said Pingleton. Patients can feel as if their diagnosis defines their life. But that’s not how the Bible sees those with mental illness, he said.

He pointed out that many biblical characters suffered from emotional struggles. And some, were they alive today, would likely be diagnosed with mental illness.

“The Bible is filled with people who struggled with suicide, or were majorly depressed or bi-polar, he said. “David was totally bi-polar. Elijah probably was as well. They are not remembered for those things. They are remembered for their faith.”

LifeWay Research’s study was featured in a two-day radio broadcast from Focus on the Family on September 18 and 19. The study, along with a guide for pastors on how to assist those with mental illness and other downloadable resources, are posted at ThrivingPastor.com/MentalHealth.

LifeWay Research also looked at how churches view the use of medication to treat mental illness, about mental and spiritual formation, among other topics. Those findings will be released later this fall.

Methodology:

LifeWay Research conducted 1,000 telephone surveys of Protestant pastors May 7-31, 2014. Responses were weighted to reflect the size and geographic distribution of Protestant churches. The sample provides 95% confidence that the sampling error does not exceed +3.1%. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups.

LifeWay Research conducted 355 online surveys July 4-24, 2014among Protestant adults who suffer from moderate depression, severe depression, bipolar, or schizophrenia. The completed sample includes 200 who have attended worship services at a Christian church once a month or more as an adult.

LifeWay Research conducted 207 online surveys July 4-20, 2014 among Protestant adults who attend religious services at a Christian church on religious holidays or more often and have immediate family members in their household suffering from moderate depression, severe depression, bipolar, or schizophrenia.

Wednesday, September 17 2014

It's as accurate as current methods, but can also confirm recovery, researchers contend

URL of this page: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/news/fullstory_148403.html (*this news item will not be available after 12/15/2014)

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

TUESDAY, Sept. 16, 2014 (HealthDay News) -- A new blood test is the first objective scientific way to diagnose major depression in adults, a new study claims.

The test measures the levels of nine genetic indicators (known as "RNA markers") in the blood. The blood test could also determine who will respond to cognitive behavioral therapy, one of the most common and effective treatments for depression, and could show whether the therapy worked, Northwestern University researchers report.

Depression affects nearly 7 percent of U.S. adults each year, but the delay between the start of symptoms and diagnosis can range from two months to 40 months, the study authors pointed out.

"The longer this delay is, the harder it is on the patient, their family and environment," said lead researcher Eva Redei, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences and physiology at Northwestern's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

"Additionally, if a patient is not able or willing to communicate with the doctor, the diagnosis is difficult to make," she said. "If the blood test is positive, that would alert the doctor."

The study, published online Sept. 16 in Translational Psychiatry, with funding from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health and the Davee Foundation, established the test's effectiveness with 32 adults who were diagnosed as depressed and 32 nondepressed adults. All of the study participants were between 21 and 79 years old.

The test works by measuring the blood concentration of the RNA markers. A cell's RNA molecules are what interpret its genetic code and then carry out those instructions from DNA. After blood is drawn, the RNA is isolated, measured and compared to RNA levels expected in a nondepressed person's blood.

Redei's team administered the blood test to all 64 participants in the study. Then, after 18 weeks of face-to-face or phone therapy for those participants with depression, the test was repeated on 22 of them.

Among the depressed participants who recovered with therapy, the researchers identified differences in their RNA markers before and after the therapy. Meanwhile, the concentration of RNA markers of patients who remained depressed still differed from the original results of the nondepressed patients.

Three of the RNA markers in the adults who recovered remained a little different from those who were never depressed, indicating the possibility that these markers might show a susceptibility to depression, the authors noted.

Additionally, if the levels of five specific RNA markers line up together, that suggests that the patient will probably respond well to cognitive behavioral therapy, Redei said. "This is the first time that we can predict a response to psychotherapy," she added.

The blood test's accuracy in diagnosing depression is similar to those of standard psychiatric diagnostic interviews, which are about 72 percent to 80 percent effective, she said.

The findings were welcomed by one mental health expert.

"The mental health profession has, for decades, been seeking an objective measure for detecting major psychiatric disorders," said Dr. Glen Elliott, chief psychiatrist and medical director of the Children's Health Council in Palo Alto, Calif. "That the authors seem to have found a measure in such a small sample that appears to be sensitive to a specific treatment -- and a psychological intervention at that -- is striking if it holds up."

However, he noted that the small number of study participants means that it is too soon to know the significance of the findings or what the drawbacks of the test could be.

"It is too early to tell how a test of this nature -- even if proven reliable, sensitive and specific -- would be best used in a clinical setting," Elliott said. But he said the findings fit into the larger effort to personalize diagnoses and treatments based on biological data from patients.

"It is an exciting possibility that could, in theory, greatly enhance treatment efficacy and efficiency," Elliott said. "However, especially in psychiatry, we are still a long way from having a reliable product that will accomplish those goals."

The new blood test is not yet available because additional studies with large groups of people must first confirm its accuracy and effectiveness before it can be considered by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval.

Depending on funding, that could take several years, Redei said. If approved, the blood test's costs would be "in the range of other specialty tests," she said.

SOURCES: Eva Redei, Ph.D., David Lawrence Stein Research Professor of Psychiatric Diseases Affecting Children and Adolescents, Asher Center for the Study and Treatment of Depressive Disorders, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago; Glen Elliott, Ph.D., M.D., chief psychiatrist and medical director, the Children's Health Council, emeritus professor of clinical psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, and professor of clinical psychiatry, Stanford School of Medicine, Calif.; Sept. 16, 2014, Translational Psychiatry, online

HealthDay

Copyright (c) 2014 HealthDay. All rights reserved. Related MedlinePlus Pages

Monday, September 15 2014

Tuesday, July 08 2014

This ad will not display on your printed page.

The following article is located at: http://www.christianitytoday.com/le/2014/july/can-neuroscience-help-us-disciple-anyone.html

Can Neuroscience Help Us Disciple Anyone?

Brain science and the renewal of your mind.

John Ortberg

For an article about ministry and neuroscience, it seems only right to begin with Scripture. So we start with one of the great neurological texts of the Bible: "David put his hand in his bag, and took thence a stone, and slang it, and smote the Philistine in his forehead, that the stone sunk into his forehead; and he fell upon his face to the earth" (1 Sam. 17:49, KJV).

Neuroscience has gained so much attention recently that it can seem like we're the first humans to discover a connection between the physical brain and spiritual development. But way back in Bible times, before EEGs and HMOs, people had noticed that putting a rock through someone's skull tends to inhibit their thinking.

For those of us in church leadership, information about "the neuroscience of everything" is everywhere. How much do we need to know about it? What new light does it shed on human change processes that those of us in the "transformation business" need to know? Does it cast doubt on the Christian view of persons as spiritual beings who are not merely physical?

Why is Neuroscience Exploding?

Neuroscience studies the nervous system in general and the brain in particular. Neurobiology looks at the chemistry of cells and their interactions; cognitive neuroscience looks at how the brain supports or interacts with psychological processes; something called computational neuroscience builds computer models to test theories.

Most of our behavior-typing, tying a shoe, or driving-is governed by habits imprinted on our brains. So is discipleship.

Because the mind can be directed to any topic, there can be a "neuroscience" of almost any topic. Neurotheology looks at the brain as we believe, think, and pray about God. Researcher Andrew Newberg has shown the brain-altering power of such practices as prayer by looking at changes in the brain-state of nuns engaged in the practice for over 15 years as well as Pentecostals praying in tongues. It turns out that intense practice of prayer means their brains are much more impacted by their prayer than inexperienced or casual pray-ers. To find out who the true prayer-warriors in your church are, you could hook everybody up to electrodes, but it might be a little embarrassing. Paul Bloom pointed out that we shouldn't be surprised by this; the surprising thing would be if people experience a profound state without their brains being affected.

Brain studies made steady progress through the twentieth century; my own original doctoral advisor at Fuller Seminary was Lee Travis, who pioneered the use of the electroencephalogram at the University of Iowa in the 1930s. But for a long time, no one could actually look inside a working brain to watch it in operation.

That changed in the 1990s with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), which allows researchers to track the flow of oxygen-rich blood (a proxy for neuron activity) in real time. Now it became possible to find out what part of the brain is involved in any given sequence of conscious activity, and how brain functions of liberals versus conservatives or religious versus non-religious people may differ from each other. It also became possible to find out if that guy in the second row whose eyes are closed when you're preaching really does have something going on in his brain during the sermon.

Why I'm Thankful for Neuroscience

"All truth is God's truth," Augustine said, and a deep part of what it means to "exercise dominion" is to learn all we can about what God has created. And there is very little God created that is more fascinating or more relevant to our well-being than our brains.

Neuroscience has immense potential to relieve human suffering. Already neuroscientists have found ways to alleviate symptoms of Parkinsons and create cochlear implants. Our church had a baptism service recently and several of those being baptized were young adults who suffer from cognitive challenges. In each case their parents were in tears. For those of us doing ministry to be aware of advances in brain science is part of caring for those in our congregation.

Research into the teenage brain made clear that the human brain isn't really fully developed until people are well into their twenties. Previously it was thought that the teenage brain was just "an adult brain with fewer miles on it." It turns out that the frontal lobes, which are associated with choosing and decision-making as well as with impulse-control and emotional management, are not fully connected—they lack the myelin coating that allows efficient communication between one part of the brain and another.

Christians have brains and neurons that are as fallible as atheist neurons and new age neurons.

This helps explains the ancient mantra of parents and student ministry leaders everywhere: "What were you thinking?" Churches can help parents of teenagers understand why a practice as simple as insisting their teenage children get a good night's sleep is so necessary. They can also help parents set expectations for their teenagers' emotional lives at an appropriate level. They can also remind church leaders who are doing talks for teenagers to keep them short!

Neuroscience can also teach us compassion. For too long people who suffered from emotional or mental illness have been stigmatized. Churches—which should have been the safest places to offer healing and care—were sometimes among the most judgmental communities because it was assumed that if people simply got their spiritual lives together, their emotions should be fine.

Rick and Kay Warren noted after the death of their son: "Any other organ in my body can get broken and there's no shame, no stigma to it. My liver stops working, my heart stops working, my lungs stop working. Well, I'll just say, 'Hey, I've got diabetes, or a defective pancreas or whatever,' but if my brain is broken, I'm supposed to feel shame. And so a lot of people who should get help don't."

Pastors can offer great help to their congregation when we simply acknowledge the reality that followers of Jesus do not get a free pass from mental health problems. Christians have brains and neurons that are as fallible as atheist neurons and New Age neurons.

Beyond that, I'm thankful for neuroscience because it is helping us understand better how our bodies work, and that enables us better to "offer our bodies a living sacrifice to God." Knees that spend long hours in prayer change their shape. So do brains.

The Limits of Neuroscience

One of the reasons it's important for pastors to be conversant with the topic is that neuroscience is being accorded enormous authority in our day—not always for good reasons. I joke with a neuroresearcher friend of mine (who helped a lot with this article but wants to remain anonymous) that the easiest way to get an article published today is to pick any human behavior and …

- Show which parts of the brain are most active when thinking about that topic;

- Explain why evolutionary psychology has shown that behavior is important to our survival;

- Give four common-sense tips for handling that behavior better—none of which has anything to do with #1 or #2.

Precisely because neuroscience has so much prestige, those of us who teach at churches need to be aware of its limitations as well as its findings. It's one thing to say that our brain chemistry or genetic predisposition may affect our attitudes or beliefs or behaviors. It's another thing to say we are nothing but our brain chemistry.

Sometimes writers make claims in popular literature that would never make it into a peer-reviewed academic journal. One example is a recent book, We Are Our Brains, which makes the claim that there is no such thing as free will, that our brains predetermine everything including our moral character and our religious leanings, so there is no good reason to believe God exists either.

Because neuroscience has so much prestige, we church leaders need to be aware of its limitations as well as its findings.

People may be under the impression that "science" has proven this. This is sometimes called "nothing buttery"; the idea that we are "nothing but" our physical selves.

Yet let's be clear: we are not just our brains.

No one has ever seen a thought, or an idea, or a choice. A neuron firing is not the same thing as a thought, even though they may coincide. A brain is a thing, a human being is a person.

God doesn't have a brain, Dallas Willard used to say, and he's never missed it at all. (Dallas actually used to say that's why for God every decision is a "no-brainer," but I will not repeat that because it's too much of a groaner, even for Dallas.)

Neuroscience can help us understand moral and spiritual development. It shows the importance of genetic predispositions in areas of character and attitudes—from political orientation to sexuality. But it has not shown that personal responsibility or dependence on God are irrelevant. It does not replace the pastor or trump the Bible.

The Neuroscience of Sin And Habits

Neuroscience has shown us in concrete ways a reality of human existence that is crucial for disciples to understand in our struggle with sin. That reality is this: mostly our behavior does not consist of a series of conscious choices. Mostly, our behavior is governed by habit. Most of the time, a change of behavior requires the acquisition of new habits. Willpower and conscious decision have very little power over what we do.

A habit is a relatively permanent pattern of behavior that allows you to navigate life. The capacity for habitual behavior is indispensible. When you first learn how to type or tie a shoe or drive a car, it's hard work. So many little steps to remember. But after you learn, it becomes habitual. That means it is quite literally "in your body" (or "muscle memory"). At the level of your neural pathways. Neurologists call this process where the brain converts a sequence of actions into routine activity "chunking."

Chunking turns out to be one of the most important dynamics in terms of sin and discipleship. Following Jesus is, to a large degree, allowing the Holy Spirit to "re-chunk" my life. This is a physical description of Paul's command to the Romans: " … but be transformed by the renewing of your mind."

Habits are enormously freeing. They are what allows my body to be driving my car while my mind is planning next week's sermon.

But sin gets into our habits. This is the tragedy of fallen human nature. Self-serving words just come out of my mouth; jealousy comes unbidden when I meet someone who leads a larger church or preaches better; chronic ingratitude bubbles up time and again; I cater to someone I perceive to be attractive or important.

Neuroscience research gives us a clearer picture (and deeper fear) of what might be called the "stickiness" of sin. It is helping us to understand more precisely, or at least more biologically, exactly what Paul meant when he talked about sin being "in our members." He was talking about human beings as embodied creatures—sin is in the habitual patterns that govern what our hands do and where our eyes look and words our mouths say. Habits are in our neural pathways. And sin gets in our habits. So sin gets in our neurons.

Like so much else, our neurons are fallen, and can't get up. They need redemption.

The Neuroscience of Discipleship

You can override a habit by willpower for a moment or two. Reach for the Bible. Worship. Pray. Sing. You feel at peace with God for a moment. But then the sinful habit reemerges.

Habits eat willpower for breakfast.

When Paul says there is nothing good in our "sinful nature," he is not talking about a good ghost inside you fighting it out with a bad ghost inside you. Paul is a brilliant student of human life who knows that evil, deceit, arrogance, greed, envy, and racism have become "second nature" to us all.

Sanctification is, among other things, the process by which God uses various means of grace to re-program our neural pathways. This is why Thomas Aquinas devoted over 70 pages of the Summa Theologica to the cultivation of holy habits.

It's why 12-step groups appeal, not to willpower, but to acquiring new habits through which we can receive power from God to do what willpower never could.

Neuroscience has helped to show the error of any "spirituality" that divorces our "spiritual life" from our bodies. For example, it has been shown that the brains of healthy people instructed to think about a sad event actually look a lot like the brains of depressed people.

"Spiritual growth" is not something that happens separate from our bodies and brains; it always includes changes within our bodies. Paul wrote, "I beat my body to make it my slave"—words that sound foreign to us, but in fact describe people who seek to master playing the cello or running a marathon. I seek to make the habits and appetites of my body serve my highest values, rather than me becoming a slave to my habits and appetites. What makes such growth spiritual is when it is done through the power and under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Paul's language remains unimprovable: We offer our bodies as living sacrifices so that our minds can be renewed.

One of the great needs in churches is for pastors and congregations to experiment with discipleship pathways that address the particular context that we face. Pornography (and misguided sexuality in general) has always rewired the brain. But now porn is so incredibly accessible that men and women can be exposed to it any time they want for as long as they want as privately as they want. Each time that connection between explicit images and sexual gratification is established, the neural pathway between the two grows deeper—like tires making ever-deepening ruts in a road.

Simply hearing that sexual sin is bad, or hearing correct theological information, does not rewire those pathways. What is required is a new set of habits, which will surely include confession and repentance and fellowship and accountability and the reading of Scripture, through which God can create new and deeper pathways that become the new "second nature," the "new creation."

At our church not long ago, one of our members spoke openly about many years of shame around sexual addiction. His courageous openness stilled the congregation, and it led to the formation of a recovery ministry that is one of the most vibrant in our church.

The Neuroscience of Virtue

Kent Dunnington has written a wonderfully helpful book, Addiction and Virtue. He notes that many federal health institutes and professional organizations assume addiction is a "brain disease" purely "because the abuse of drugs leads to changes in the structure and function of the brain." However, playing the cello and studying for a London taxi license and memorizing the Old Testament also lead to changes in the structure and function of the brain. Shall we call them diseases, too?

Dunnington says that addiction is neither simply a physical disease nor a weakness of the will; that to understand it correctly, we need to resurrect an old spiritual category: habit. We have habits because we are embodied creatures; most of our behaviors are not under our conscious control. That's a great gift from God—if we had to concentrate on brushing our teeth or tying our shoes every time we did that, life would be impossible.

But sin has gotten into our habits, into our bodies, including our neurons.

Partly, we may be pre-disposed to this.

For example, people with a version of the Monoamine oxidase A (MOA) gene that creates less of the enzyme tend to have more troubles with anger and impulse control. (If you have that version of MOA, you're feeling a little testy right now.) This means that when Paul says "In your anger, do not sin," some people are predisposed to struggle with this more than others.

That doesn't mean that such people are robots or victims or not responsible for their behavior. It does explain part of why Jesus tells us to "Judge not"; none of us knows the genetic material that any other person is blessed with or battling in any given moment.

This also shows that the people in our churches will not be transformed simply by having more exegetical or theological information poured into them—no matter how correct that information may be. The information has to be embodied, has to become habituated into attitudes, patterns of response, and reflexive action.

The reason that spiritual disciplines are an important part of change is that they honor the physical nature of human life. Information alone doesn't override bad habits. God uses relationships, experiences, and practices to shape and re-shape the character of our lives that gets embedded at the most physical level.

A few decades ago scientists did a series of experiments where monkeys were taught how to pinch food pellets in deep trays. As the monkeys got faster at this practice, the parts of the brain controlling the index finger and thumb actually grew bigger. This and other experiments showed that the brain is not static as had often been thought, but is dynamic, able to change from one shape to another. This is true for human beings as well. The part of violinists' brains that controls their left hand (used for precise fingering movements) will be bigger than the part that controls their right hand.

But wait—there's more. In another study, people were put into one of three groups; one group did nothing; one exercised their pinky finger, a third group spent 15 minutes a day merely thinking about exercising their pinky finger. As expected the exercisers got stronger pinkies. But amazingly—so did the people who merely thought about exercising. Changes in the brain can actually increase physical strength.

No wonder Paul wrote: "Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is pleasing, whatever is commendable, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things." Every thought we entertain is, in a real sense, doing a tiny bit of brain surgery on us.

Here's a thought worth contemplating: what must Jesus' brain have been like? Imagine having neural circuits honed and trained to trust God, to respond to challenge with peace, or to irritation with love, or to need with confident prayer.

Here's another thought worth contemplating: We have the mind of Christ.

That's worth wrapping your brain around.

John Ortberg is pastor of Menlo Park Presbyterian Church in California.

Copyright © 2014 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal.

Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.

Thursday, May 08 2014

'Love Addiction': Biology Gone Wrong?

Deborah Brauser

May 07, 2014

NEW YORK ― "Love addiction," a condition characterized by severe pervasive and excessive interest toward a romantic partner, may actually be a form of attachment disorder, new research suggests.

A new literature review of studies using the terms "love addiction," "pathological love," and "behavioral addiction" showed possible involvement of the brain reward dopaminergic system as well as attachment-related biological systems.

"We wondered where does love, a feeling of well-being, devolve into addiction? And what might be the criteria for love addiction and its destructive and dysfunctional behaviors?" asked Vineeth P. John, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, during a press briefing here at the American Psychiatric Association 2014 Annual Meeting.

Still, he told Medscape Medical News that it is important not to medicalize normal, albeit deep, love. Instead, clinicians should be concerned if patients stay in a relationship despite danger or if have severe pining long after a breakup despite knowing the relationship is over.

"There is an urgent need for a better conceptualization of [love addiction] from a nosological and neurobiological perspective," the investigators note.

"This would be the first step in devising controlled studies aiming at properly assessing the efficacy of different psychosocial and pharmacological interventions in the treatment of this intriguing condition."

Lack of Control

Dr. John reported that the researchers wanted to question whether being addicted to love was possible and if so, whether it could be a diagnosable disorder.

They defined love addiction as a pattern of maladaptive behaviors and intense interest toward 1 or even more romantic partners at the detriment of other interests and resulting in a lack of control and significant impact on functionality.

Although it can occur simultaneously with substance dependence or sex or gambling disorders, it can also be considered an addiction behavior itself, a part of a mood or obsessive-compulsive disorder, or even a part of erotomania.

"It is thought that it affects as many as 3% of the population. And in certain subsets of young adults, it may even go up to 25%," said Dr. John.

He added that individuals who are most at risk for the condition include those with an immature concept of love, a maladaptive social environment, or high levels of impulsivity and anxiety; are anxious-ambivalent or "seductive narcissists"; or have structural affective dependence.

Results from the analysis showed that a picture of a participant's "beloved" elicited activation in the brainstem, the right ventral tegmental area (VTA), and the caudate nucleus regions. These areas have been shown to be central to the brain's reward, memory, and learning functions and have been implicated in substance abuse.

In addition, addiction and attachment disorders share overlapping neural circuits, through the VTA to the nucleus accumbens.

"So basically, what we might be looking at is an attachment problem," he said.

Love Molecules

He also reported that 4 possible "molecules of love" include dopamine (which incites desire and facilitates repetition of love behavior), oxytocin (which mediates social behavior), the opioid hormone (which activates pleasure sensations), and vasopressin (which affects protective behaviors).

Interestingly, men who carried the "allele 334 for the gene coding for vasopressin receptor (AVP R1A)" showed less stable relationships.

"But the most plausible and practical aspect of love addiction would be to look at how to treat it," said Dr. John.

Because they found few studies examining benefits of psychotherapy and no studies assessing the efficacy of medications for this condition, the investigators came up with hypothetical guidelines for target symptom interventions.

For psychosocial treatments, they suggested self-help groups, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, or enrolling in Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous.

In addition, they suggested using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and/or antidepressants to treat obsessive thoughts about a romantic partner; mood stabilizers to treat mood instability or seeking out multiple partners; mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, naltrexone, or buprenorphine for treating impulsive seeking of romantic partners; and oxytocin or vasopressin for treating impaired attachments.

"It might be possible to devise drug-based therapies for the treatment of difficult love, based on neurobiological substrates," said Dr. John.

"But this is clearly a futuristic concept. We cannot medicalize noble human emotions. This particular addiction has to be harmful, disruptive, and destructive and cause significant psychological distress. And the treatment has to be totally voluntary," he added.

"Overall, it's time to think about our patients, or at least a small subset of them who are clearly suffering with what is probably an attachment problem."

Worth Pursuing

"I think this is a very important area of study," said Jeffrey Borenstein, MD, president and CEO of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation in New York City.

"The issue of attachment is extremely important because it relates to other conditions that we treat, including some of the personality disorders," he added.

Dr. Borenstein, who was not involved with this research, was moderator of the press briefing.

He noted that the investigators' approach of looking specifically at the question of love addiction was interesting.

"Obviously Dr. John is not saying that we have pills for this or even that we should be treating this. But I think it's an area of study worth learning more about," concluded Dr. Borenstein.

The study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

American Psychiatric Association's 2014 Annual Meeting. Abstract NR8-35. Poster presented May 6, 2014.

Medscape Medical News © 2014 WebMD, LLC

Send comments and news tips to news@medscape.net.

Cite this article: 'Love Addiction': Biology Gone Wrong? Medscape. May 07, 2014.

Thursday, March 27 2014

Your Brain as a Car

- Driver sits on the Front left side

- Thinks

- Makes Decisions

- Freewill sits in this sit

- This part controls the wheel, brakes, and gas

- The Adult part of the brain

- Is confused or overwhelmed by stress

- Stress comes from outside/other drivers

- Stress comes from inside/other passengers

- Bottom line Behavior sits in this seat—this is what you do

- The Navigator sits on the right front side

- This is your conscience

- Your moral values and belief system resides here

- This is your Parent within

- This part has the map and looks where you have been, where you are, and where you are heading

- It influences the Driver by telling the Driver what it Believes you should be doing

- It feels guilty about the past (what you did or did not do)

- It feels worried or concerned about the present (what you are doing or not doing)

- It feels anxious about the future (where you are or are not heading)

- It is in continual dialogue with the Driver while keeping alert and watchful of the other passenger in the backseat

- The Child sits in the backseat

- All the primary emotions of anger, fear, and joy reside here

- Anger, fear, and joy can be combined to make all the other emotions

- The child sits in front of a surround sound movie screen that has all the memories/movies of the past

- Movies/memories can be past, present, or future if stored as real

- The child does not know the difference between real and imagined

- The child thinks in pictures, images, and emotions but not so much in words

- The child sees what is going on in the front seat and senses if the two adults in the front are in agreement

- The child also looks out the window of the car but sees like a child and not an adult

- The emergency brake—the fight/flight mechanism is in the backseat with the child

- Therefore the child does not drive the car but can cause it to brake and can hijack the brain

- The child is not immoral but amoral

- The child moves towards pleasure and away from pain

- Memories of pain are stored in twice the chemical quantity as pleasurable memories at the cellular level

- The child works on Feelings and emotions regardless of whether they are real or not they are real to the child

- Congruence or harmony is where the Adult, Parent, and Child are in agreement

- All information comes into and is screened by the amygdala—the part that directs all sensory data throughout the brain

- The wiring from the amygdala is shorter to the back of the brain—the child, then the front of the brain—the adults

- Therefore we react before we think and are then left to explain are actions to ourselves and others

- As a man/person thinks in his heart (his inner child) so is he

- Out of the heart (the inner child) the mouth speaks

- In Romans 7:14-28 Paul describes the conflict between the child and the adult parts of the brain

- In Romans the 8th chapter he describes how we have to learn to walk by the Spirit and not be sight

- The insula is the GPS or God Positioning System that fires into the gut

- Our gut level feelings are up to 70% accurate

- Decisions made in the brain and not the gut are only on the average 25% accurate

- We need to learn to trust our gut

- The insula is more active and developed in people who meditate and pray

- Bottom line: All parts of the brain need to listen to the insula and learn to trust our gut

Monday, August 12 2013

August 12, 2013, 2:53 pm

A Glut of Antidepressants

By RONI CARYN RABIN

Over the past two decades, the use of antidepressants has skyrocketed. One in 10 Americans now takes an antidepressant medication; among women in their 40s and 50s, the figure is one in four.

Experts have offered numerous reasons. Depression is common, and economic struggles have added to our stress and anxiety. Television ads promote antidepressants, and insurance plans usually cover them, even while limiting talk therapy. But a recent study suggests another explanation: that the condition is being overdiagnosed on a remarkable scale.

The study, published in April in the journal Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, found that nearly two-thirds of a sample of more than 5,000 patients who had been given a diagnosis of depression within the previous 12 months did not meet the criteria for major depressive episode as described by the psychiatrists’ bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (or D.S.M.).

The study is not the first to find that patients frequently get “false positive” diagnoses for depression. Several earlier review studies have reported that diagnostic accuracy is low in general practice offices, in large part because serious depression is so rare in that setting.

Elderly patients were most likely to be misdiagnosed, the latest study found. Six out of seven patients age 65 and older who had been given a diagnosis of depression did not fit the criteria. More educated patients and those in poor health were less likely to receive an inaccurate diagnosis.